Configurational cluster expansion formulation

Configurational effective Hamiltonian

A configurational effective Hamiltonian expresses the energy of a crystal as a function of the occupation of the sites of the crystal:

\[E = f(\sigma_{1}, \dots, \sigma_{n}, \dots, \sigma_{N}),\]where

- $E$ is the energy of a microstate.

- $\vec{\sigma} = (\sigma_{1}, \dots, \sigma_{n}, \dots, \sigma_{N})$ is a “configuration”, a vector that represents the occupation on sites of the crystal. It is associated with a particular microstate.

- $N$ is the total number of sites.

When is this a good approximation?

- A configurational effective Hamiltonian is a good approximation for properties that depend on ground state properties and configurational entropy.

- In systems where configurational entropy dominates, an configurational effective Hamiltonian can provide a good prediction of the phase diagram, lattice constants, band gap, and other quantities.

- In systems where electronic and vibrational contributions cannot be ignored, predictions from an configurational effective Hamiltonian may still be an important starting point to which other contributions can be added.

What does an occupation variable, $\sigma_{n}$, represent?

Distinct occupation values may represent:

- Different chemical species

- Discrete, distinguishable properties:

- Discrete charge states

- Discrete magnetic moments

- Discrete molecular orientations

- etc.

How many distinct configurations are there?

- For a binary system there are $2^N$ configurations, for a ternary $3^N$, for a quaternary $4^N$, etc. if all occupant types are allowed on all N crystal sites.

- However, in a crystal, a number of these configurations will be equivalent due to symmetry.

- The next section uses a simple example to demonstrate how to take advantage of symmetry when constructing an effective Hamiltonian.

Tensor product expansion

Ground state properties of a crystal, such as energy or volume at zero Kelvin, can be expressed as a function of the type of occupant on each site in the crystal.

Note: It is assumed that there are some boundary conditions, such as zero pressure, or fixed crystal shape, and that atomic positions are relaxed locally to minimize the energy of the system while those boundary conditions are maintained.

Given an appropriate choice of initial crystal, in most cases the atoms will stay close enough to the original site that the site occupations are a good label for the ground state. In some cases, an initial state may involve atoms relaxing so far they end up closer to a different crystal site. In these cases, the ground state is most appropriately labeled with a different occupation.

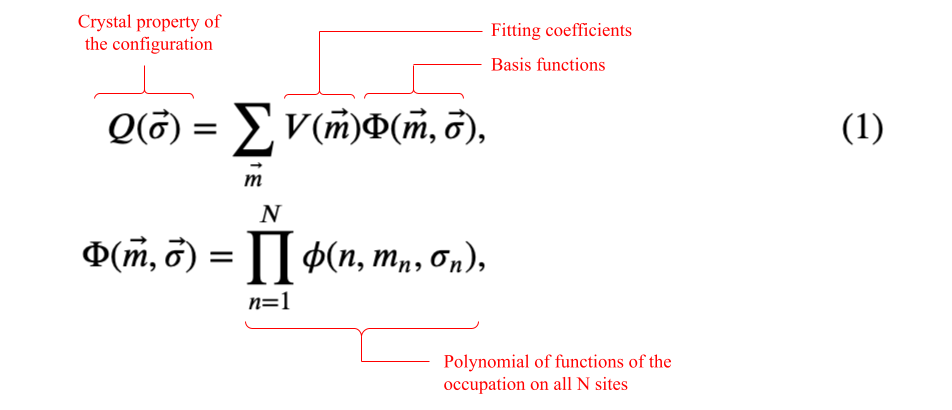

A general tensor product expansion has a basis set consisting of polynomial functions of the value of the occupation of all sites in the crystal:

where:

- $Q(\vec{\sigma})$ is a property of the crystal microstate, $\vec{\sigma}$ (ex. formation energy)

- $\vec{m}=(m_{1}, \dots, m_{n}, \dots, m_{N})$ is a vector of indices that labels a particular crystal basis function

- $m_{n}$ has possible values:

- $[0,1]$ on a site with two allowed occupants

- $[0,1,2]$ on a site with three allowed occupants

- $[0,1,\dots,M-1]$ on a site with $M$ allowed occupants

- The number of possible $\vec{m}$ equals the number of possible configurations

- $\Phi(\vec{m},\vec{\sigma})$ is a crystal basis function. A crystal basis function is a polynomial of site basis functions, including one from every crystal site.

- $\phi(n,m_{n},\sigma_{n})$ is the $m_{n}$-th site basis function of the occupation value on site $n$

- $V(\vec{m})$ are fitting coefficients

Note that Eq. (1) is completely general; it does not include any consideration of symmetry. Sanchez et al. [2] showed how contruct a complete, orthogonal basis set that takes advantage of crystal symmetries and can be extended to any number of components.

Binary alloy on 4 sites

The primitive description

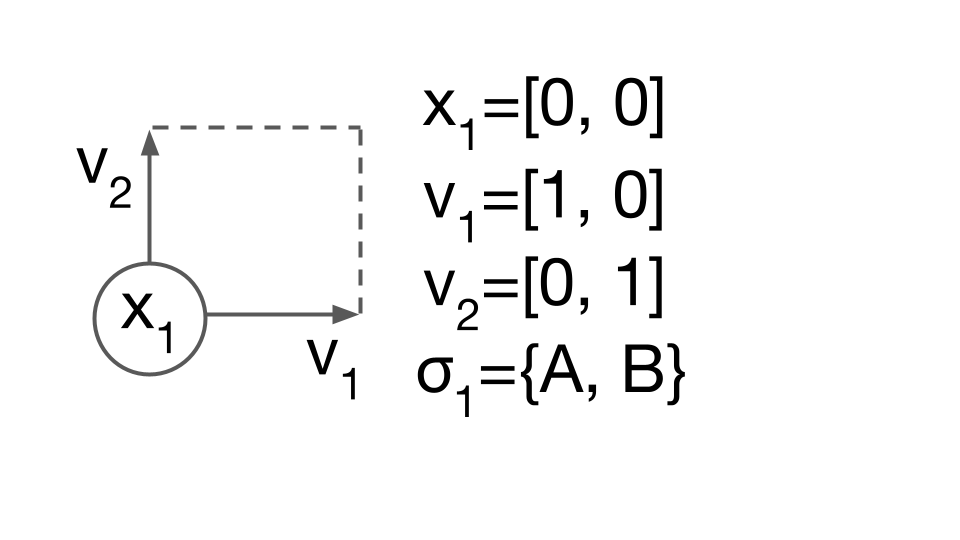

Consider using Eq. (1) to describe a finite “binary alloy” of species A and B, in a perfect 2 dimensional square arrangement. The primitive description of this system includes the lattice vectors, $v_1, v_2$, the position of the site, $x_1$, and the species allowed on the site, $\sigma_1={A,B}$. In CASM, this primitive description of the crystal structure and allowed degrees of freedom (DoF) is called the “prim”.

Enumeration of configurations

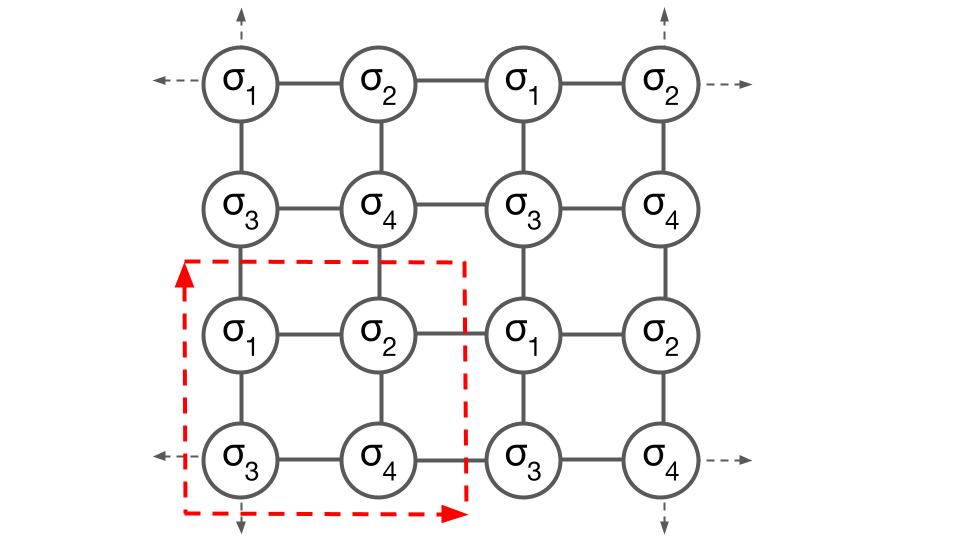

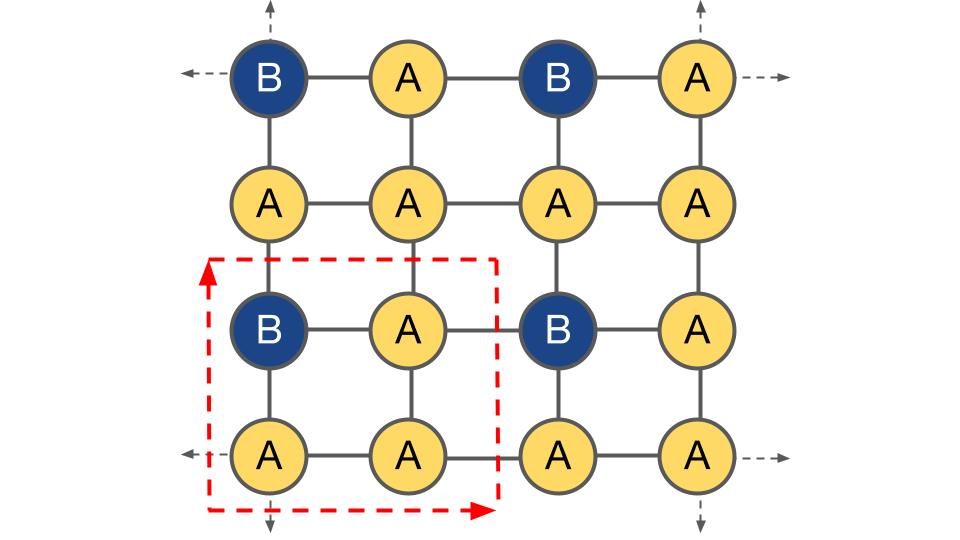

Next consider a square supercell of the “prim”, with four sites labeled as follows:

The specification of a supercell of the prim restricts configurations to particular symmetries and a limited number of orderings, but does not yet specify any particular ordering.

To specify a particular configuration, the value of the occupant at each site within the supercell must be specified. In the following example, the configuration is $[B, A, A, A]$:

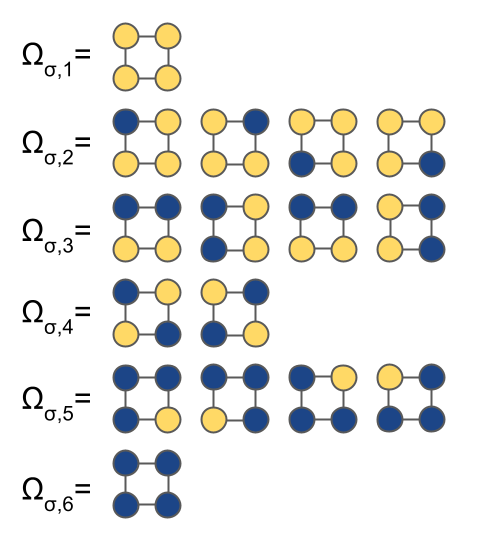

Within this supercell, there are six “orbits” of symmetrically unique configurations, $\Omega_{\vec{\sigma}}$:

Basis set construction - Site basis functions

Site basis functions provide support for the, in this example, $2^N=16$ polynomial functions, needed to form a complete basis for the properties of the $2^N=16$ possible configurations.

To select suitable site basis functions, $\phi(n, m_{n}, \sigma_{n})$, note that since all sites are symmetrically equivalent, $\phi$ does not vary with $n$. In a crystal with multiple sublattices, we may need different $\phi$ on each sublattice.

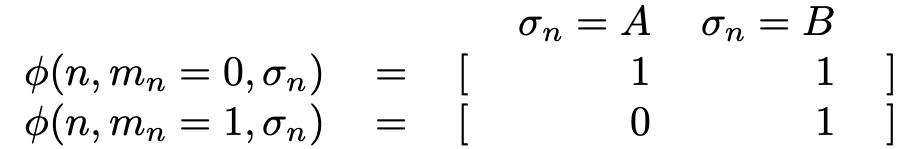

Given that symmetry constraint, there are still many possible choices of site basis functions. For this example, we choose “occupation” site basis functions with values either 1 or 0 according to the table:

As we will see, this choice results in an expansion around the properties of the pure A configuration. Other choices of site basis functions can result in an expansion around other configurations, the random alloy, a particular set of average sublattice compositions. Depending on the use case, a good choice of site basis functions may result in faster convergence of the expansion.

Basis set construction - Cluster basis functions

To write the general tensor product expansion for the system, Eq. (1), consider the occupant indices, $\vec{m}$. These indices enumerate all the possible ways the occupants might interact. In other words, there is one $\vec{m}$ (i.e. $[1, 0, 0, 0]$) for each configuration, $\vec{\sigma}$ (i.e. $[B, A, A, A]$).

In this supercell there are $2^4=16$ possible values of $\vec{m}$: $[0, 0, 0, 0]$, $[0, 0, 0, 1]$, $[0, 0, 1, 0]$, $\dots$, $[1, 1, 1, 1]$.

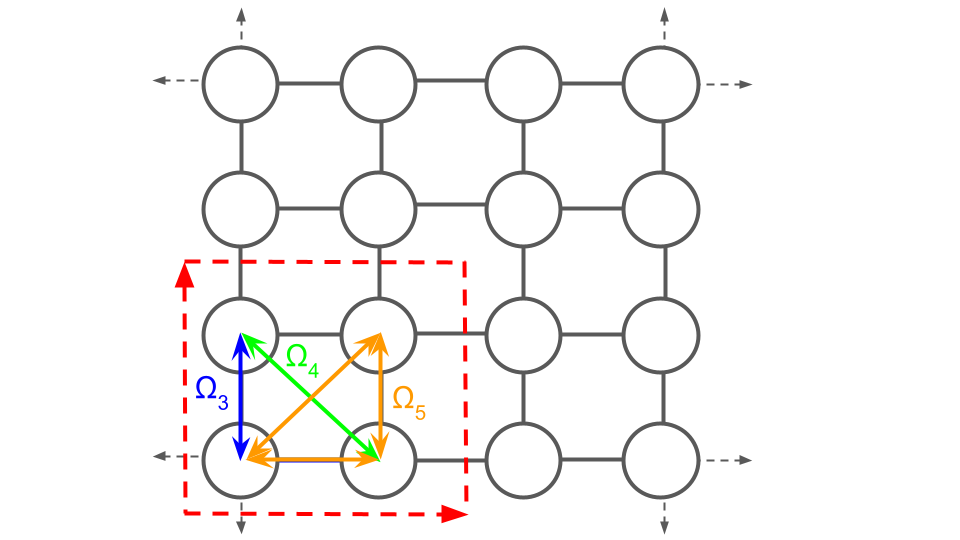

Symmetry results in there being six orbits, $\Omega$, of equivalent vectors of $\vec{m}$, each of which label an orbit of crystal basis functions which must have equivalent interactions:

- $\Omega_{1}$: $[0, 0, 0, 0]$

- $\Omega_{2}$: $[1, 0, 0, 0]$, $[0, 1, 0, 0]$, $[0, 0, 1, 0]$, $[0, 0, 0, 1]$

- $\Omega_{3}$: $[1, 1, 0, 0]$, $[1, 0, 1, 0]$, $[0, 1, 0, 1]$, $[0, 0, 1, 1]$

- $\Omega_{4}$: $[1, 0, 0, 1]$, $[0, 1, 1, 0]$

- $\Omega_{5}$: $[1, 1, 1, 0]$, $[1, 1, 0, 1]$, $[1, 0, 1, 1]$, $[0, 1, 1, 1]$

- $\Omega_{6}$: $[1, 1, 1, 1]$

The fitting coefficients, $V(\vec{m})$, for all $\vec{m}$ in the same orbit must have the same value. Thus, symmetry has shown that rather than needing as many as $2^N=16$ fitting coefficients, this system needs at a maximum only 6 coefficients to fit all possible values of a particular property.

Note also that using $\sigma_n = 0$ to represent species A, $\sigma_n = 1$ to represent species B, the orbits $\Omega$ also label the possible configurations.

When storing configurations in a project, CASM by convention keeps only the “canonical form” of symmetrically equivalent configurations, defined as the occupant labels, $\vec{m}$, that has the highest lexicographical order.

As an example, the configuration $[1, 0, 0, 0]$ is the canonical form of the equivalent configurations in the orbit $\Omega_{2}$ because of the lexicographical comparison $[1, 0, 0, 0] \gt [0, 1, 0, 0] \gt [0, 0, 1, 0] \gt [0, 0, 0, 1]$.

Following the choice of $\phi$ and enumeration of $\vec{m}$, we can write out all of crystal site basis functions:

- $\Omega_{1}$: $1$

- $\Omega_{2}$: $\sigma_1, \sigma_2, \sigma_3, \sigma_4$

- $\Omega_{3}$: $\sigma_1 \sigma_2, \sigma_1 \sigma_3, \sigma_2 \sigma_4, \sigma_3 \sigma_4$

- $\Omega_{4}$: $\sigma_1 \sigma_4, \sigma_2 \sigma_3$

- $\Omega_{5}$: $\sigma_1 \sigma_2 \sigma_3, \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \sigma_4, \sigma_1 \sigma_3 \sigma_4, \sigma_2 \sigma_3 \sigma_4$

- $\Omega_{6}$: $\sigma_1 \sigma_2 \sigma_3 \sigma_4$

where for the sake of clarity we take advantage of the fact that for a binary alloy $\sigma_n$ can be used as shorthand for $\phi(0, 1, \sigma_{n})$.

By choosing a constant value of $\phi=1$ for $m_n=0$, the expansion no longer need to explicitly evaluate the value of the site basis functions at every site. The crystal basis functions now only depend on particular clusters of sites and can be call cluster basis functions.

A “prototype” is one instance of an object in an orbit, from which the rest of the orbit can be generated. Protoype clusters of the pair cluster orbits associated with $\Omega_{3}$ and $\Omega_{4}$, and the triplet cluster associated with $\Omega_{5}$ are shown in the following:

Basis set evaluation

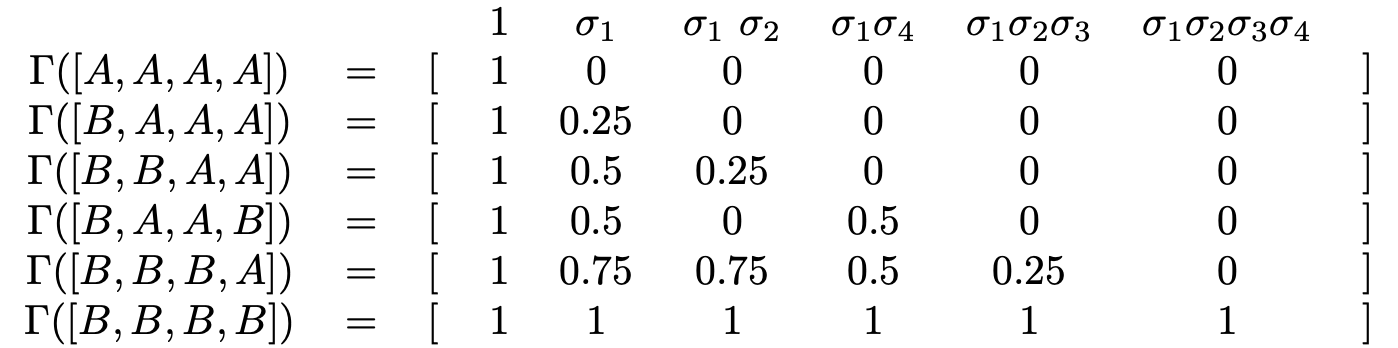

Next we define the “correlations”, $\Gamma_\alpha(\vec{\sigma})$, the average value of an orbit of crystal basis functions:

\[\Gamma_\alpha(\vec{\sigma}) = \sum_{\delta \in \Omega_{\alpha}} \frac{1}{N^{\alpha}}\Phi_{\delta}(\vec{\sigma}),\]where:

- $\Phi_{\delta}(\vec{\sigma})$ is a particular cluster basis function in the $\Omega_{\alpha}$ orbit

- $N^{\alpha}$ is the number of cluster basis functions in the orbit $\Omega_{\alpha}$.

Thus, a vector of correlations can be calculated that is identical for each symmetically equivalent configuration. In this system, with the choice of “occupation” site basis functions, the correlations (with columns labeled by a “prototype” cluster basis function in the corresponding orbit) are:

This table is the correlation matrix for the six symmetrically unique configurations.

Fitting coefficients

Fitting coefficients can then be determined for any property (the fully relaxed energy, volume, elastic moduli, bandgap, etc.) that depends on the configuration $\vec{\sigma}$. Using energy as the example, the fitting coefficients can be determined by solving:

\[E_{s} = X_{s,\alpha} * V_{\alpha}\]where:

- $s$ is a configuration index, indicating both a particular configuration ($\vec{\sigma}_{s}$) and the fully relaxed microstate associated with that configuration

- $\alpha$ is a cluster basis function orbit index

- $E_{s}$ is the fully relaxed energy of the microstate $s$

- $X$ is a correlation matrix, with row $s$ being $\vec{\Gamma}(\vec{\sigma}_{s})$, the correlation vector for configuration $s$

- $V_{\alpha}$ is the fitting coefficient for cluster basis function orbit $\alpha$. It is a convention in the materials science field to call the fitting coefficients “effective cluster interactions” (ECI).

Cluster expansion effective Hamiltonian

From the previous example, it should be clear that the proper choice of site basis functions and use of symmetry allows writing a cluster expansion effective Hamiltonian as:

\[\begin{eqnarray*} q(\vec{\sigma}) = v_{0} + \sum_\alpha v_{\alpha} \Gamma_\alpha(\vec{\sigma}), \tag{2} \\ \Gamma_\alpha(\vec{\sigma}) = \frac{1}{N^{\alpha}} \sum_{\delta \in \Omega_{\alpha}} \Phi_{\delta}(\vec{\sigma}), \\ \Phi_{\delta}(\vec{\sigma}) = \prod_{\phi_{n,m_{n}} \in \delta}\phi_{n,m_{n}}(\sigma_n) \end{eqnarray*}\]where:

- $q(\vec{\sigma})$ is an intrinsic property of the crystal microstate, $\vec{\sigma}$ (ex. formation energy per unit cell)

- $\Omega_{\alpha}$ is the $\alpha$-th orbit of symmetrically equivalent cluster basis functions

- $N^{\alpha}$ is the number of cluster basis functions in the $\Omega_{\alpha}$ orbit

- $v_{\alpha}$ are fitting coefficients, called “effective cluster interations” (ECI), associated with the $\Omega_{\alpha}$ orbit

- $\Gamma_\alpha(\vec{\sigma})$ are “correlations”, the average value of the $\Omega_{\alpha}$ orbit of cluster basis functions

- $\Phi_{\delta}(\vec{\sigma})$ is a particular cluster basis function in the $\Omega_{\alpha}$ orbit

- $\phi(n,m_{n},\sigma_{n})$ is the $m_{n}$-th site basis function on site $n$

A cluster expansion is often a good choice for an effective Hamiltonian because:

- It forms a complete and orthonormal basis over configurational space, meaning that given a good choice of fitting coefficients, a good fit to $e^{f}_{s}(\sigma)$ is possible.

- It is sufficiently efficient to evaluate with high predictive accuracy. Chemical interactions generally fall quickly with site distance, allowing the expansion to be truncated without significant loss of accuracy. Other types of interactions, such as due to strain and electronic chage, may be long ranged and fall off slowly. There are also reciprocal-space formulations of the cluster expansion that have been developed to treat long-range interactions.

- It is invariant with respect to the application of crystal symmetry operations. This means that if a symmetry operation transforms $\vec{\sigma_{s}} \to \vec{\sigma_{s^{\prime}}}$, then $f(\vec{\sigma_{s}})=f(\vec{\sigma_{s^{\prime}}})$ and the predicted properties of the crystal will have the correct symmetry.

References

- A. Natarajan, J. C. Thomas, B. Puchala, and A. Van der Ven, Phys. Rev B 96, 134204 (2017). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.96.134204

- J. M. Sanchez, F. Ducastelle, D. Gratias, Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 128, 334 (1984).

- A. Van der Ven, J. C. Thomas, B. Puchala, A. R. Natarajan, Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 48 10.1–10.29 (2018)